Why Government Spending Is Bad for the Economy

On Monday, President Biden announced $42 billion in funding to build internet infrastructure across the country, with the goal of getting every American connected to the internet by 2030. This is the “largest internet funding announcement in history,” the White House proudly noted, comparing it to FDR’s Rural Electrification Act of 1936, which provided federal loans that helped bring electricity to rural areas of the US.

Officially known as the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) program, the initiative aims to bring high-speed internet to the roughly 8.5 million households and small businesses that are still lacking this infrastructure. “High-speed internet is no longer a luxury,” the White House said. “It is necessary for Americans to do their jobs, to participate equally in school, access health care, and to stay connected with family and friends.”

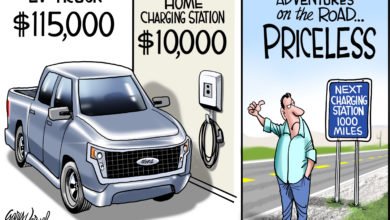

While it’s easy to see the benefits of increased internet access, the price for taxpayers isn’t exactly cheap. Doing the math, Rep. Thomas Massie pointed out that it will cost about $4,941 for each family that is connected to the internet. By contrast, Elon Musk’s Starlink can do the job for $599 per family, he noted.

Today Biden announced $42 billion to get 8.5 million families broadband by 2030.

— Thomas Massie (@RepThomasMassie) June 28, 2023

Come on man! That’s $4,941 per family, to be taken from those families and other families in taxes.@elonmusk’s Starlink can do it for $599 per family, and you don’t have to wait 7 years! pic.twitter.com/vUdS5eBgD0

Implementation questions aside, it’s worth asking, is this a good policy? Is it wise for the government to be spending money on these kinds of projects in general? Well, I suppose it depends on what we mean by “good.” If “good” means funneling money to special-interest groups—as pretty much all government spending is designed to do—then yes, it will do that quite well. But if it means beneficial for the welfare of the masses, there are good reasons to believe spending projects like this actually work against that aim rather than facilitate it.

To understand why, we need to discuss a bit of economics.

The ‘Miracle’ Unmasked

One of the most important concepts in economics is the idea of scarcity. Our wants exceed our resources, which means there will always be trade-offs. Money spent on one initiative is money that can’t be spent elsewhere. There is no such thing as a free lunch.

This is just as true for government spending as it is for anything else. Though it’s easy to focus on the benefits—in this case, the internet infrastructure that would be created—the good economist trains himself to see the hidden costs, the lost opportunities, the things that could have been funded and would have been built if only the money hadn’t been spent on the project in question.

Henry Hazlitt stressed this point in his book Economics in One Lesson. “Either immediately or ultimately,” he wrote, “every dollar of government spending must be raised through a dollar of taxation. Once we look at the matter in this way, the supposed miracles of government spending will appear in another light.”

Though everyone would agree in principle that you can’t get something for nothing, it seems this truth gets completely forgotten the moment government spending comes up. “How could you be against internet infrastructure?” people might say. “Don’t you care about internet access?” Of course I do. But I also recognize that money spent on internet access is money that can’t be spent on food, healthcare, education, or housing. And unlike the proponents of these programs, I don’t presume to know what consumers most urgently need.

If people are managing fine without the internet but are desperate for more healthcare services, spending resources on more internet when those resources could have been used for more healthcare isn’t really helping. To take an extreme example, if I thought people really needed more pineapples, I could spend billions of dollars on pineapple infrastructure. And it’s true, there would be much better access to pineapples. But think of all the waste! So many more important things could have been created with those resources, but instead the most urgent wants are left unfulfilled because some politician thought pineapples were a higher priority for those funds than anything else.

The question, then, is not whether internet access is important. The question is whether it is more important than the alternatives. The mere existence of a benefit justifies nothing. The benefit must outweigh the cost. It must be more important than the opportunities that are foregone to achieve it.

So, how do we systematically determine which uses of resources are the most valuable to consumers? With the government, this is impossible. Politicians and planners are simply “groping in the dark,” as the economist Ludwig von Mises put it. Sure, they’ve got all sorts of statistics, but the statistics paint at best a blurry picture of the relative needs of consumers.

Fortunately, there is an alternative: the market. On the market, profits and losses signal to entrepreneurs the relative value consumers place on different goods and services. These signals lead to a remarkable coordination between the needs of consumers and what gets produced. It’s not perfect, of course, but at least there is a mechanism for rationally allocating resources to meet the most urgent needs of consumers as best as possible.

Government spending is at best a zero-sum game. It is taking resources that could have been used on one thing and using them on something else instead. But in practice it’s almost always worse than that, because market allocations tend to reflect the needs of consumers far better than government allocations. Thus, government spending inevitably wastes resources, directing them to the proverbial pineapple industry rather than the things consumers need most.

And it’s not like this issue can just be fixed with better managers. The managers aren’t the problem. It’s the system that’s the problem. As the economist Murray Rothbard noted in Power and Market, “The well-known inefficiencies of government operation are not empirical accidents, resulting perhaps from the lack of a civil-service tradition. They are inherent in all government enterprise.”

Capitalists: Informed Humanitarians

When free-market proponents push back on government spending initiatives like the recent internet access program, we are often accused of being “against” whatever that initiative is trying to achieve. In this case, people will probably say we are “against internet access.” Here Biden is trying to do something nice to improve the welfare of American citizens, and we just want to stop him, presumably because we are heartless souls who hate paying taxes and don’t care about other people’s well-being.

But this is simply a leftist narrative, one that has little basis in reality. Frédéric Bastiat called out this kind of thinking in his 1850 book The Law.

“Socialism, like the ancient ideas from which it springs, confuses the distinction between government and society. As a result of this, every time we object to a thing being done by government, the socialists conclude that we object to its being done at all. We disapprove of state education. Then the socialists say that we are opposed to any education. We object to a state religion. Then the socialists say that we want no religion at all. We object to a state-enforced equality. Then they say that we are against equality. And so on, and so on. It is as if the socialists were to accuse us of not wanting persons to eat because we do not want the state to raise grain.”

The fact is, free-market proponents do care about human welfare. In fact, it is precisely because we care that we are against government spending! The question is not whether to have government-funded initiatives or let people suffer, but whether to have the government or the market allocate resources.

A proper understanding of economics, we believe, leads to the conclusion that market allocations tend to be better for the well-being of everyone than government allocations. Thus, far from being an act of misanthropy, our opposition to government spending actually stems from the very concern for human welfare that the left erroneously thinks they have a monopoly on.

This article was adapted from an issue of the FEE Daily email newsletter. Click here to sign up and get free-market news and analysis like this in your inbox every weekday.

Content syndicated from Fee.org (FEE) under Creative Commons license.

Agree/Disagree with the author(s)? Let them know in the comments below and be heard by 10’s of thousands of CDN readers each day!