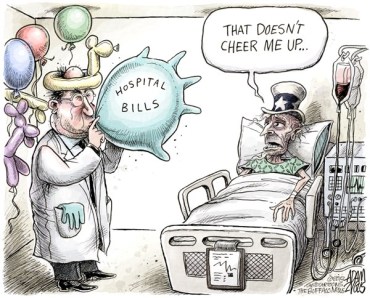

Hospitals Guard Prices Like the CIA Guards Secrets

Way back in 2017, before we were on the Road to Nuremberg With Donald Trump, the Washington Post was outraged that hospitals were trying to make a profit. Like most stories involving reporters, economics and healthcare it was both wildly inaccurate and agenda–driven.

The story’s one useful service was it introduced the public to the slightly ominous term “Chargemaster.” At first glance, the term “Chargemaster” might be mistaken for the cause of the so–called epidemic of “mass incarceration.” A fiendish device district attorneys use to jail minorities captured during the government’s regular sweeps in low–income areas.

Even for those who haven’t been to jail, the term has unsavory associations bringing to mind arrogant, price–gouging, monopolies who look upon customers as rubes to be exploited. (Ticketmaster, come on down!)

In reality, the “Chargemaster” has more to do with pricing than policing. Theoretically, it’s a complete listing of all the services and procedures a hospital provides patients, followed by the cost for each item.

What the consumer doesn’t know is the price listed after any procedure is as hyperbolic as an entree description on a Trump restaurant menu. The cost paid by Medicare or a health insurance company often bears little relation to what’s listed on the Chargemaster. Just as the window sticker on a new car is only a starting place in the negotiation.

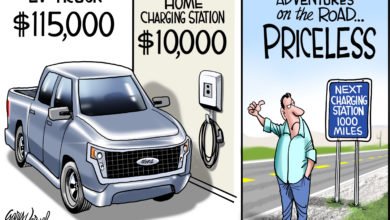

The US healthcare market is currently designed to guarantee high prices, encourage waste and discourage price shopping. That’s because consumers can get a binding estimate on building a house, but they can’t get any kind of estimate on removing a gall bladder. Requiring hospitals to post the Chargemaster on the web is supposed to give consumers this vital information, but in truth all it will give most of them is a headache.

I predict it will be easier to read the privacy agreement for Facebook victims than it is to comprehend the Chargemaster. If it were up to hospital administrators consumers wouldn’t even be able to find out what it cost to park until they tried to exit the lot. Instead of a simple procedure equals cost equation, the consumer will no doubt have to assemble the procedure himself, which is just how the hospitals want to keep it.

Maryland made a tentative effort to lift the cost veil. The Maryland Health Care Commission has a website with the inane name of “Wear the Cost,” which sounds like the surgery bill will be tattooed on your backside. Instead, it compares turnkey prices for common procedures affecting patients who are either women, old or both.

Consumers who fit within that medical straightjacket can finally see what hip replacement, knee replacement, hysterectomy and vaginal delivery prices are at 21 different hospitals. Unfortunately, hospital patients, like whiskey drinkers, tend to associate high cost with high quality. That’s not necessarily true as the medical complication and readmission rates for the procedures at various hospitals demonstrates.

Patients can have high–quality care for lower cost if they will only do their research among these limited options.

The feds need to build on the Chargemaster unveiling by demanding all hospitals that accept federal money post binding prices on the web for the 25 most common surgical procedures; the 25 most common outpatient procedures and the 25 most common tests. The listed, turnkey charges must also match the best price offered insurance companies.

That’s half the battle. The other half is getting the consumer to act on the information. In Maryland Sinai Hospital charges $32,500 for a knee replacement, while UMD Medical Center at Easton charges over one–third less at $22,700, with fewer readmissions. If the patient has a $3,000 deductible and the co–pay is 10 percent, many would still choose the more expensive Sinai because it wipes out their deductible and all the rest that year’s healthcare is ‘free’!

Smart insurance companies would give the patient an incentive to be a smart shopper by sharing the savings. Instead of pocketing the $9,800 saved by paying for the knee replacement at UMD Easton, the insurance company could share by applying ten percent of the savings to the patient’s deductible for that year.

The patient would pay ten percent of the procedure ($2,270) and the insurance company would apply ten percent of the savings ($980) and their deductible for the year would be satisfied. To ensure this wasn’t a one–time–only cost–conscious decision by the consumer, the insurer could continue to apply ten percent of procedure savings to future deductibles. This is good for the company because it reduces customer churn by giving the patient a reason not to change policies and the customer saves money on future deductibles.

That’s an ideal situation. What we have is Confusionmaster and that’s probably where the feds will call it quits.