Trump’s Executive Actions Cannot Undo the Wrong of Obama’s

Whether executive orders are constitutional is something of a thorn in the side of political theorists. There is nothing in the Constitution that strictly forbids the use of unilateral executive action; in fact, the Constitution explicitly grants the president a limited degree of such power in order to clarify and direct the internal operations of federal agencies. However, the Constitution also expressly forbids all powers not enumerated in its text to the federal government and reserves them for state and local levels, a phrase which suggests the Founders would not be pleased with either the actions presidents take or the sense of entitlement as an end-run around the checks and balances with which presidents undertake them.

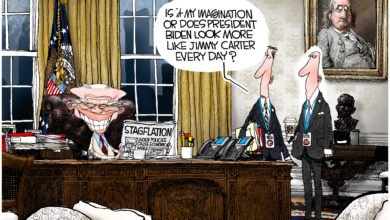

The middle-ground for this spectrum of hazy legality is the oft-cited notion that presidents who use executive actions to supplement or define already existing laws are within the bounds of their Constitutionally-delineated power. The legal murkiness, however, has made the nature of executive power a perennial source of rancor, one which former President Obama who touted his use of his pen and his phone did little to assuage.

Nor does it look likely that President Trump will be any less controversial with his use of executive action. On the first working day of his presidency, Trump will establish a precedent of executive activism which continues the precedent set by his antecedent, reportedly issuing orders on a range of topics from the economy and trade to the location of the Israeli embassy.

What is significant about Trump’s actions is that many of them will be directed against executive orders issued by predecessors, a move which has led many on the right to cheer and many on the left to cry foul. In some ways, this is the much awaited “I told you so” moment for conservatives who opposed Obama’s executive activism as unconstitutional. They warned liberal supporters that, though they might like the policies Obama was pursuing, they might not like what a future president could justify doing by citing the precedent created by Obama.

This would seem to be an absolutist stand against unilateral federal action by the right. Sadly, however, there is vocal support for the dismantling of the Obama agenda, particularly the former president’s signature healthcare legislation, through executive action. They are focused on the content of the action, not the proper use of authority at its root.

Essentially, this is political relativism. To overlook the dubious legality of the president’s unilateral action simply because it reverses a policy which is personally distasteful is to ground politics in partisan agendas. It is to enshrine not egalitarian principles as the fountainhead of moral authority but to empower subjective interpretations of ideological motives as ultimate arbiters of policy. It is to create a system where every four or eight years, a new paradigm emerges as what is considered just and fair shifts in response to the personal views of the president.

While there is a progressive process of erosion of existing political practices which must occur over time to bring about such a political culture, this is not a straw man. The normalization of practices that were formerly outside the realm of acceptance can be seen in the mainstream right’s acceptance of Trump’s executive agenda. And this trend will only continue; the more a practice occurs without push back, the more legitimacy it gains as a normal part of the political process.

This is significant because it undermines the argument that Trump’s use of executive power is acceptable if he only uses it to reverse the unconstitutional actions Obama took. In doing so, Trump legitimizes the use of the power, thus undercutting his position and at the same time buoying the notion that executive orders are a legitimate path for accomplishing ends which a president cannot achieve by working in concert with the legislative branch.

Further, with this precedent established, it takes a great deal of will for a president to discontinue governing via unilateral executive action, which is doubly problematic considering executive unilateralism makes more room for personality in governance and considering the current president is one whose leadership strengths lie more in personality than in ideology?

“Personally distasteful” ? Is it really ‘his’ wish to use executive orders …OR has he heard the people’s voices and finds this the most expedient method to let people know he is listening? Of course we shouldn’t discount the known fact that most often Congress moves at the speed of molasses on a cold day in Vermont……Leadership is exhibited often in attitude and action. This would seem to show both a ‘can do, will do’…..and it’s legal