The Great Financial Replacement: Is America Adopting a New Currency?

For starters, the U.S. Federal Reserve System, coupled with public sector banks around the world, has been gradually hinting at the possibility of introducing CBDC.

A CBDC is an electronic or “digital” form of traditional money issued and governed by a country’s central bank; it is tied to fiat currency in the national unit, such as the U.S. dollar. A CBDC differs from other digital currencies or “cryptocurrencies” that operate under autonomous communities instead of a centralized system.

There is no shortage of media outlets focused on financial services examining the various “benefits” of CBDC. According to the International Monetary Fund, a major United Nations’ financial agency headquartered in Washington D.C., the advantage of a centralized digital form of money can promote “financial inclusion” by serving unbanked or underbanked populations and “lead to better access to money, increase efficiency in payments, and in turn lower transaction costs.”

Create a targeted CBDC welfare payment

Beginning October 10 through 16, the annual meeting between the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group (WBG) took place in person in Washington D.C.

Continuing the theme of financial inclusion, Deputy Managing Director Bo Li expressed that CBDC can be harnessed through “programmability.” This would allow government agencies and private sector players to program a contract and “precisely target their support to those people who need support,” such as a welfare payment or a food stamp coupon.

Just so everyone is clear, Li reportedly worked at the People’s Bank of China before joining the IMF. So, to this end, how relevant are the IMF and WBG particularly to the United States?

-

Given 195 countries, 190 are members of the IMF, and this international financial institution is reportedly governed by and accountable to these countries. Moreover, it reportedly supports economic policies that “promote financial stability and monetary cooperation,” such as a foreign exchange transaction system to foster investment, expansion of international trade and global economic growth.

-

Meanwhile, the WBG is a world-leading development bank that comprises five organizations and reportedly aims “to end poverty and boost prosperity for the poorest people.” While headquartered in Washington D.C., the WBG has 189 member countries, with the U.S. as the bank’s largest shareholder.

Every new idea aims to be sold to the masses as a “solution to a problem,” and the masses have to believe that the stated “problem” exists and absolutely believe that this new idea is part of “progress” in society.

Make no mistake. The IMF-WBG partnership is absolutely, unequivocally, determined to support the global integration and normalization of CBDC. The question is, will the American people embrace and accept this new form of digital currency?

CBDC is of global interest

Indeed, a report by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) released in May shows that around 90 percent of 81 surveyed central banks “are exploring CBDCs, and more than half are developing them or running concrete experiments.”

And to emphasize the global level of research and pilot tests around centralized digital currencies, a website coined “CBDCTracker” provides relevant updates and news worldwide.

-

While the Federal Reserve has “made no decisions on whether to pursue” a CBDC, it does state that “as a liability of the Federal Reserve, however, a CBDC would be the safest digital asset available to the general public, with no associated credit or liquidity risk.”

-

Similarly, the United Kingdom (U.K.’s) Bank of England is “looking carefully” at how CBDC might work for the general public but “have not yet made the decision to introduce one.”

-

The European Central Bank (ECB) has been more open about its ambitions. A new report released (again) in May marks the beginning of a 2-year project’s investigation phase since July 2021, aiming “to develop a safe, efficient, and accessible form of digital central bank money.”

Indeed, automated teller machines (ATMs) are globally on the decline. For instance, Sweden might be heading towards a cashless society as only 13 percent of the nation used cash in 2018, and only 11 percent of payments at a U.K. store in 2021 involved cash. Moreover, the U.S. ATM manufacturing industry’s market size has declined by around 5 percent per year over the last five years. That said, the ATM count increased by 3,000 in 2021, possibly due to restarting machines that were deactivated during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Sail through “choppy waters“ in economy using CBDC

The IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, decided to justify CBDC by metaphorically viewing the currency as “a new fleet of ships,” designed to withstand world economy challenges represented by an old ship in “choppy waters.” These ships representing CBDC would “take people on new voyages” by opening up new possibilities—and because central banks issue CBDC, “they offer more confidence that the ships would move safely.”

But then again, Georgieva didn’t seem to understand why not enough consumers, as she would preferably like, are using existing alternatives such as digital “e-” wallets on mobile “smartphones” that are designed to store money. Georgieva probed:

Is it lack of trust in the [digital] payment service providers? Is it a preference for informality? Is it difficulty to access services, or it is that it costs a little bit more for people for whom every penny counts? We need to understand that so we can then make a proper, um, information provision that covers for people—how not using cash is better to protect yourself against crime, and how if you use digital money you can graduate from payments to credit and that, of course, enhances financial inclusion.

How about “is it a preference for privacy” by having cash on hand or gold locked in safe storage?

Protecting anonymity and privacy

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said at the Banque de France conference in late September that if CBDC is pursued, he would be “looking to balance privacy protection with identity verification” and that it “would not be anonymous” like cryptocurrencies.

Christine Lagarde, president of the ECB, echoed a similar point at the conference, stating that with a digital euro currency, “there would not be complete anonymity as there is with…bank notes.” However, she then added, “There would be a limited level of disclosure and certainly not at the central bank level.”

All the above begs the following question. Will the integration of CBDC increase government prying into our financial purchases and transactions, which could then be used to discriminate or favor access to future credit cards or bank loans, or at the furthest end, influence access to leisure services or employment opportunities?

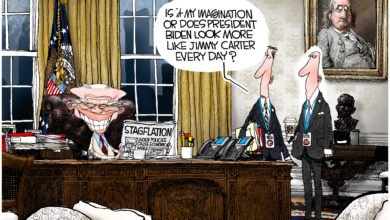

The Biden administration’s reaction to CBDC

In early March, President Joe Biden signed an executive order calling for more research on developing a digital U.S. currency through the Federal Reserve. The order also highlighted the need for government oversight of cryptocurrencies, which, despite fluctuating popularity for investment purposes, have also been widely used for criminal activities, such as money laundering. In contrast to CBDC, one of the reported benefits of cryptocurrencies is decentralization. However, according to Investopedia, such transactions leave a digital trail that the Federal Bureau of Investigation can decrypt.

Later that same month, four Democratic representatives introduced a bill that would allow the U.S. Treasury—as opposed to the Federal Reserve—to create and issue a digital dollar. In this case, the digital dollar would be “token-based” and held on a person’s card or phone. Therefore, losing that item with the stored tokens accounts for a complete loss of funds.

The ECASH Act (Electronic Currency And Secure Hardware Act) proposes that payments be functionally identical to cash and support peer-to-peer, anonymous cryptocurrency transactions. In addition, the bill wouldn’t require payment processing intermediaries; thus, transactions would be “instantaneous,” and processing fees likely reduced.

We’ll see.

But people who care about their right to personal privacy, in how they choose to own, store and use their financial wealth, might want to really pay attention to the evolution of CBDC.

Be prepared for the attempt to mainstream CBDC

Let’s just get something really straight. According to the think tank Atlantic Council, 105 countries representing over 95 percent of global GDP, are exploring a CBDC. Presently, 50 countries are in an advanced exploration phase, i.e., development, pilot or launch.

The United States is currently in a CBDC research phase. China, in contrast, is presently in the pilot stage. Although the Red Dragon is also experiencing fast adoption of smartphone payments instead of credit or debit cards, it’s a different story for Uncle Sam.

Indeed, many Americans do not trust major smartphone payment “apps” due to security concerns. In addition, those aged 50 and older are more likely to distrust apps like PayPal, Venmo, Zelle and CashApp with their money than their younger counterparts.

It is arguably the case that the credit and debit card system is well-established, and it’s quicker to swipe a card than to find the right payment app installed on a smartphone. Plus, it’s probably a good idea to have an external card or, better still, cash on hand, given the scenario that a smartphone is lost, stolen or malfunctions.

But given the above, the IMF’s deputy managing director commented that a CBDC ecosystem does not even require a smartphone and that such digital currencies can potentially help those “without internet access, without a phone because CBDC can be stored in a store value card.”

In other words, there is no intention of backing away from countries that might be slightly hesitant towards embracing CBDC. Every hesitation will be explored, challenged and attempted to be resolved. Do not be surprised if we start observing a carefully crafted—and lengthy—campaign that aims to gain the American people’s trust around transitioning from traditional money to CBDC marked as “progress.”

Cash is still used but is declining as the preferred payment method

According to a new Pew Research Center survey published in early October, 41 percent of 6,034 U.S. adults said that none of their purchases in a typical week is paid for using cash, an increase from 29 percent in 2018. Conversely, 59 percent of respondents said that all, almost all or some purchases are paid for using cash.

Among those surveyed, 58 percent of Americans said they try to make sure they always have cash on hand. However, upon deeper inspection, 54 percent of 18 to 49-year-olds aren’t worried about whether or not they have cash since they can use other payment methods. In wide contrast, 71 percent of respondents aged 50 or older try to ensure they always have cash on hand.

The IMF will want to understand any lingering, mild or strong preference for cash and then aim to extinguish that preference. Another challenge lies in the hesitancy among some customers and merchants to join the CBDC ecosystem, as the IMF’s deputy managing director pointed out—and then proposed a solution:

We need a better understanding of what’s the cause, what’s driving that hesitancy. One way to solve it relates back to our data question. That is, if we can create enough value—if by joining this ecosystem, if the consumer can enjoy a lot more financial services, if they can get credit—they may be willing to join the [CBDC] ecosystem, right?

Organizations dedicated to steering the world in a direction that aligns with a vision of growing centralization, where the concept of “personal privacy” is as foreign as aliens from Mars visiting Earth—are not backing down. And nor should Americans who value the right to privacy as ingrained in their God-given liberty.

Content syndicated from Dear Rest of America with permission

Agree/Disagree with the author(s)? Let them know in the comments below and be heard by 10’s of thousands of CDN readers each day!