Why Is Bill Gates Amassing Large Amounts of Farmland While Advocating for “Synthetic Meat” in America?

William Henry Gates III, better known as Bill Gates, recently won a legal approval to buy around 2,100 acres of North Dakota farmland valued at $13.5 million. According to the 2021 edition of the Land Report 100, he is considered the largest private owner of farmland in America with now over 270,000 acres. At the same time, Gates has been advocating for developed nations to consume “synthetic meat” to fight climate change.

Meanwhile, a congressman from South Dakota is demanding that Gates explain his farmland purchases. Understandably, many will question the motivations of one of the world’s wealthiest business magnates with an estimated net worth of $110 billion.

So let’s explore Gates’ appetite for buying up so much U.S. farmland and pushing for the consumption of “meat” that isn’t meat.

Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, also founded Cascade Investment, L.L.C in 1995. Over time, he sold personal stock in Microsoft and reinvested it through Cascade Investment.

From its earliest inception, Cascade Investment focused on blue chip defensive stocks—large companies with solid brands and consistent earnings—including Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts, Coca-Cola and investor Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Gates and Buffett are close friends, and Cascade Investment embraced Buffet’s approach to holding stocks long-term for handsome returns.

While Gates worked on diversifying his portfolio, he also established the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) with his then-wife in 2000, merging the William H. Gates Foundation and the Gates Learning Foundation. Buffet has also served on the trustee board, which has since grown to hold nearly $70 billion in investable assets.

According to the BMGF website, the foundation’s role, mainly aiming at developing countries, is to “give every person a chance at a healthy, productive life.” Moreover, the foundation’s work “depends on grantees and partners across the United States and in more than 130 countries who have on-the-ground expertise, a deep understanding of the issues we care about.”

One way or another, the BMGF has never shied away from making the headlines.

In 2009, the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), a Seattle-based non-government organization, launched a $3.6 million Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine trial funded by the BMGF. Around 25,000 Indian girls aged 10 to 14 in tribal communities were involved in the study. Yet, the Indian government terminated the project after several months when news outlets reported the deaths of seven girls.

The Parliament of India released a report in 2013 condemning PATH for “irregularities and discrepancies” in the study; it asserted that “the safety and rights of the children in this vaccination project were highly compromised and violated.” PATH had failed to obtain the proper informed consent from the participants’ parents.

For Gates, it was business as usual. In a 2019 Wall Street Journal article, he wrote that a $10 billion investment into vaccine technology was the “best investment” he had ever made. That same month, Gates echoed the success of his decision-making from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland: “We feel there’s been over a 20-to-1 return,” yielding $200 billion over the last twenty years.

Indeed, let us not forget Event 201, a simulation about a coronavirus pandemic just months before the reported outbreak of COVID-19, hosted by Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in partnership with the World Economic Forum and the BMGF. Then, in December 2020, the BMGF announced a $250 million commitment, building upon the foundation’s total investment of $1.75 billion toward fighting the COVID-19 pandemic through vaccine development and distribution.

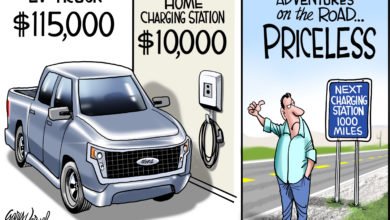

Farmland falls under the “alternative asset,” a type of investment outside stocks, bonds or cash investments. Other alternative assets include hedge funds, real estate, natural gas, fine art, rare wines and cryptocurrencies.

For investors heavily invested in the stock market, a benefit of alternative assets is the potential to diversify their portfolios outside the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ—and a helpful safety net should the stock market crash. Thus, investing in farmland could deliver more profitable and consistent returns when inflation rises, especially when traditional assets tend to be impacted. Moreover, there are reported advantages of tax savings.

Indeed, Gates’ wallet is already deep in the agriculture sector. It was revealed in 2010 that the BMGF had purchased 500,000 shares of the agrochemical business Monsanto, worth around $23 million. Monsanto once dominated America’s food chain with its genetically modified (GM) seeds but faced fierce criticism for unethical practices and became defunct in 2018.

Dr. Phil Bereano is a Professor Emeritus and recognized expert on genetic engineering from the University of Washington; he cut straight to the chase after learning about Gates’ investment in 2010. “First, Monsanto has a history of blatant disregard for the interests and well-being of small farmers,” he said. “The strong connections to Monsanto cast serious doubt on the Foundation’s heavy funding of agricultural development in Africa.”

Having transitioned toward owning large plots of farmland, Gates has also emerged as one of the world’s leading voices for a particular type of synthetic food.

According to Gates, we must abandon real meat to save the planet—but we’ll get to his reasoning in a moment.

Two types of synthetic alternatives attempt to mimic meat. “Cultivated meat” or “cultured meat” is laboratory-grown from genuine animal cells, whereas “plant-based meat” is made from plants rich in protein, such as beans, lentils, tofu and nuts.

In 2017, Cargill Inc., one of the largest global agricultural companies, joined Gates and fellow billionaire Richard Branson to invest in technology that cultivates meat from self-renewing animal cells called “stem cells.”

Indeed, Berkeley-headquartered Upside Foods, then known as Memphis Meats, reportedly raised $17 million. The company produces “chicken” in devices called “bioreactors” from the cells extracted from living chickens, i.e., without slaughtering poultry.

In a February 2021 interview with MIT Technology Review, Gates pointed out what wealthier countries should be doing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and help to combat climate change:

I do think all rich countries should move to 100% synthetic beef. You can get used to the taste difference, and the claim is they’re going to make it taste even better over time. Eventually, that green premium is modest enough that you can sort of change the [behavior of] people or use regulation to totally shift the demand. So for meat in the middle-income-and-above countries, I do think it’s possible.

Gates also said that since cows emit a greenhouse gas called “methane,” beef must be produced using synthetic proteins:

There are all the things where they feed them [livestock] different food, like there’s this one compound that gives you a 20% reduction [in methane emissions]. But sadly, those bacteria [in their digestive system that produce methane] are a necessary part of breaking down the grass. And so I don’t know if there’ll be some natural approach there. I’m afraid the synthetic [protein alternatives like plant-based burgers] will be required for at least the beef thing.

Indeed, the Los Angeles–based producer Beyond Meat, which is backed by Gates and a notable investment of Cascade Investment, reportedly became a “$550 million brand” after producing a plant-based “burger” that emulated the appearance of a burger that sometimes bleeds. The GM-free, soy-free gluten-free meat alternative was made using pea protein, beet coloring and beet juice and was popular among enthusiastic meat-eaters.

While investments are pumped into producing meat alternatives, some researchers have questioned their environmental and health impact.

Not really, according to Marco Springmann, a senior environmental researcher at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom. He expressed in mid-October 2019:

Lab meat doesn’t solve anything from an environmental perspective, since the energy emissions are so high. So much money is poured into meat labs, but even with that amount of money, the product still has a carbon footprint that is roughly five times the carbon footprint of chicken and ten times higher than plant-based processed meats.

Springmann was referring to the rise of the “cultured meat” industry that could arguably worsen carbon emissions while aiming to lower methane gas emissions.

Moreover, according to a research study published in February 2019 by Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, the large-scale production of such meat alternatives might lead to carbon emissions that could be just as harmful as greenhouse gas emissions from livestock.

The study highlights that the carbon emissions produced from manufacturing laboratory-grown “meat” stay in the atmosphere for centuries. Conversely, methane emission produced by raising and slaughtering livestock fades from the atmosphere after 12 years.

John Lynch, a researcher at Oxford University and co-author of the publication, expressed that:

If these companies want to sell cultured meat as an environmental alternative, they will need to look at renewable energy resources for production. They need to have the drive to do it…The interest of the companies is making it clear how will they produce in an environmentally sustainable way.

In the last two years, mainstream health-based articles highlighting the benefits of cutting down on meat, meatless diets or “synthetic meat” have been all the rage. Yet even as late as 2019, there were articles indicating caution and skepticism.

Gates’ $13.5 million investment in nearly 2,100 acres of northeast North Dakota land reportedly outraged locals, who feel they are being exploited by the ultra-rich. Yet, in late June, the state’s Republican Attorney General Drew Wrigley had issued a letter stating the deal complied with a 1932 archaic anti-corporate farming law. The Depression-era law prohibits corporations or limited liability companies from owning farmland or ranchland but allows individual trusts to own the land under the condition that it is leased to farmers.

Soon afterwards in mid-July, Republican Rep. Dusty Johnson of South Dakota wrote a letter to the House Agriculture Committee chairman David Scott, stating that:

I believe that Mr. Gates’ holdings [of farmland] across much of our nation is a significant portion that the Committee should not ignore. The Committee should be interested in Mr. Gates’ ownership and plans for his acreage, as he has been a leading voice in the push for ‘synthetic meat’.

Johnson also took to Twitter after his letter circulated across the mainstream media:

I’m curious what’s planned for this incredibly productive ag[ricultural] land given that he [Gates] believes developed countries like America “shouldn’t eat any red meat.” How are his land purchases related to those aspirations?

Could we presume that the plants—the ingredients—used to produce these meat alternatives are or will be grown on the farmland now owned by Gates?

Could there be an intention to minimize private ownership of agricultural land and create rentals instead? Would those “renting” a plot of Gates’ farmland be subject to limitations that comply with the billionaire’s vision for Americans to consume 100 percent synthetic products that replicate the taste and consistency of real meat?

It may be said that Gates has a history of displaying a large appetite—for control and influence.

In mid-May 1998, the Department of Justice filed antitrust charges against Microsoft, accusing the company of making it difficult for consumers to install competing software on computers run by its Windows operating system.

Nearly two years later, Federal Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ruled that Microsoft “maintained its monopoly power by anticompetitive means.”

In early June 2000, Jackson ordered Microsoft to be broken into two smaller companies, justifying that the company “as it is presently organized and led is unwilling to accept the notion that it broke the law or accede to an order amending its conduct.” The Harvard-educated judge added that Microsoft, “convinced of its innocence, continues to do business as it has in the past.”

The following year, a federal appeals court unanimously reversed the company breakup order, though it upheld the conclusion that Microsoft engaged in anticompetitive practices and violated antitrust law.

Jackson had some bold words about the Microsoft co-founder in a January 2001 interview with the New Yorker:

I think he has a Napoleonic concept of himself and his company, an arrogance that derives from power and unalloyed success, with no leavening hard experience, no reverses.

Following the settlement of such a high-profile antitrust case, Gates rebranded his image from being accused of creating a dictator-like monopoly to a philanthropist who wants to save humanity and planet Earth.

In the BMGF’s 2018 annual letter, Gates’ then-wife Melinda pointed out that though it’s not fair that “we have so much wealth when billions of others have so little,” the foundation’s work is to “advance equity around the world.” Gates, meanwhile, reasoned that private foundations offer a “unique role.” He reckoned that the BMGF took a long-term approach toward solving global problems and managing “high-risk projects that governments can’t take on and corporations won’t.”

Fast forward to mid-July 2022. Following Gates’ successful approval to purchase even more farmland, the billionaire tweeted that he had donated an additional $20 billion to the BMGF. He added, “As I look to the future, I plan to give virtually all of my wealth to the foundation. I will move down and eventually off of the list of the world’s richest people.”

Gates expressed his appreciation for Buffett’s “friendship and guidance,” who has reportedly donated nearly half of the resources the foundation controls. He went on to say:

I have an obligation to return my resources to society in ways that have the greatest impact for reducing suffering and improving lives. And I hope others in positions of great wealth and privilege will step up in this moment too.

In his heart of hearts, Gates might be genuinely convinced of having good intentions.

Yet the billionaire continues to connect with an international organization that has partnered with leading global companies and highly influential political figures. The World Economic Forum has claimed our taste for meat is “endangering our planet” and that we should consume 3D printed plant-based alternatives while promoting a vision where we won’t “own anything” and will borrow instead.

For the above reasons, many continue to follow the trail of Gates’ wallet.

Actions. Always. Speak. Louder. Than. Words.

Content syndicated from Dear Rest of America with permission

Agree/Disagree with the author(s)? Let them know in the comments below and be heard by 10’s of thousands of CDN readers each day!