The Atlantic Union Idea – Conveniently Forgotten History

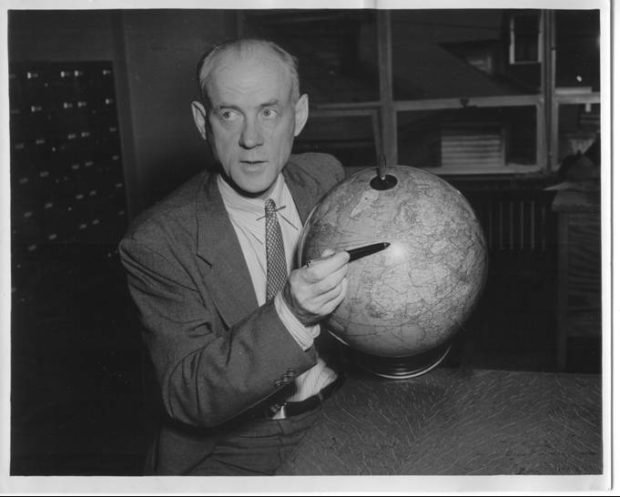

In 1949, Clarence K. Streit, author of Union Now (1939), teamed up with former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts, former Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs William L. Clayton, and former Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson to form the Atlantic Union Committee (AUC). The mission of the AUC was to enlist public support “for a resolution to be introduced in Congress inviting other democracies with whom the U.S. is contemplating an alliance [NATO], to meet with American delegates in a federal convention to explore the possibilities of uniting them in a Federal Union of the Free.” Streit and company wanted to apply the vision of our Founding Fathers on a transatlantic, and eventually world, scale.

Days after the U.S. Senate ratified the North Atlantic Treaty on July 21, 1949, Senator Estes Kefauver introduced an Atlantic Union resolution seeking to transform NATO into an Atlantic Union based on federalist principles using the constitutional convention approach. President Truman personally supported the idea, but Secretary of State Dean Acheson believed the Atlantic Union idea was a bridge too far. The U.S. State Department opposed the resolution on the grounds it was premature and would undermine their efforts to federate Europe before pursuing a more perfect Atlantic partnership.

In late 1949 and 1950, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations held hearings on a variety of world order schemes. The social-scientific consensus at the time was that the nation-state system was the root cause of war. Progressive internationalists convinced a lot of people that world federation was the only way to prevent an atomic war with the Soviet Union. Members of Congress were willing to explore the idea of working with Joseph Stalin to transform the UN into a world government.

Streit and company preferred the Atlantic Union approach to world federation because it was designed to defend and extend individual liberty, democracy, and capitalism. Grenville Clark and the United World Federalists, on the other hand, were willing to embrace coexistence with the Soviet Union to apparently save the world. Simply put, proponents of Atlantic Union placed their emphasis on advancing Western civilization while world federalists place theirs on securing general and complete disarmament and the supremacy of world law.

The Atlantic Union movement was temporarily derailed in the early 1950s due to the Korean War. President Truman opted to use the United Nations system to justify American intervention in the region to prevent the spread of communism. Under the Truman Doctrine, defending and extending individual freedom, democracy, and capitalism became a fundamental objective of American foreign policy.

In 1952, the American people headed to the polls to pick a new President—and possibly a new foreign policy direction. America could either continue to lead the free world at the expense of American blood and treasure, or restore its principled, non-interventionist roots. The question was settled within the Republican Party after the Eisenhower campaign allegedly stole the nomination from Senator Robert A. Taft—a conservative, non-interventionist who opposed NATO and the United Nations. General Dwight D. Eisenhower didn’t lead the Allies to victory during World War Two for the Soviet Union to enjoy the spoils.

Republican Party bosses picked Senator Richard M. Nixon, a cosponsor of the Atlantic Union resolution, to serve as Eisenhower’s running mate. Curiously, Democratic Party operatives denied Senator Estes Kefauver the Democratic nomination after he won most of the primaries. It seems that Democrats were not concerned about democracy back then.

Fearing the Eisenhower administration would use treaties and executive agreements to reform the UN system, form an Atlantic Union, and subsequently undermine the American Bill of Rights, Senator John W. Bricker attempted to curb the treatymaking power by reintroducing the Bricker amendment. This did not prevent Eisenhower from openly supporting UN reform efforts and quietly advancing the Atlantic Union idea. The Atlantic Union Committee helped convince Eisenhower to collude with members of the Democratic Party to kill the Bricker bill.

After President Eisenhower ended the Korean War by threatening to nuke China, he placed his emphasis on reforming the UN system. In anticipation of a General Review Conference under Article 109 of the Charter, in 1954 and 1955 the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held hearings around the country on proposals designed to strengthen the UN system. Their efforts were undermined after the Soviet Union refused to review the Charter.

To encourage transatlantic awareness and cooperation in the mid-1950s, Streit and company inspired the establishment of an annual NATO Parliamentarians Conference. In preparation for NATO’s 10th anniversary, Senator Kefauver and others convinced the 3rd NATO Parliamentarians to call for an Atlantic Congress composed of eminent citizens from NATO Nations to explore the future of the Atlantic Alliance. Before the Atlantic Congress was held, President Eisenhower replaced Secretary of State John Foster Dulles with a former cosponsor of the Atlantic Union resolution, Christian A. Herter.

In June of 1959, around 700 transatlantic elites attended the Atlantic Congress and endorsed the idea of holding a “Special Conference” to explore Atlantic unification. It was a major victory for Senator Kefauver and the Atlantic Union Committee. Proponents of Atlantic Union essentially convinced the NATO Parliamentarians and the Atlantic Congress to pressure the U.S. Congress to pass an Atlantic Union resolution.

At the behest of the Atlantic Congress, President Eisenhower instructed Secretary Herter to encourage the U.S. Congress to pass a watered-down version of the Atlantic Union resolution renamed the U.S. Citizens Commission on NATO resolution. This resolution, however, called for the exploration of Atlantic unity rather than federalism. The U.S. Congress passed the bill, and President Eisenhower signed it in June of 1960. The law authorized the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House to appoint citizen delegates to the U.S. Citizens Commission to set up and participate in the Atlantic Convention of 1962.

Intrigue emerged after the Atlantic Convention was authorized considering 1960 was an election year. The next President of the United States would be in a unique position to shape a new world order. Vice President Richard M. Nixon hoped the Atlantic Convention would call for an Atlantic Union based on federalist principles. As a Senator, Nixon was a consistent cosponsor of the Atlantic Union resolution.

Atlantic federalism was put on hold after Nixon was defeated by Senator John F. Kennedy. While Kennedy voted for the U.S. Citizens Commission on NATO resolution, he favored the federal Europe first approach to Atlantic unification. A former cosponsor of the world federalist resolution, Kennedy was destined to place his initial foreign policy emphasis on general and complete disarmament and strengthening the UN system. This was a major setback for Streit and company.

In March of 1961, Vice President Johnson and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn selected William Clayton and Christian Herter to lead the U.S. Citizens Commission on NATO. In October of the same year, Clayton and Herter called for Atlantic integration and free trade with developing nations as a communist containment strategy. Later in December, before the Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy of the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress, Clayton outlined the trade objective of the U.S. Citizens Commission on NATO when he testified as follows—

“First, I want to mention the essentiality of Western unity to Western survival. In speaking of survival, I am speaking in the sense of the cold war, under which we could lose our freedoms without a shot being fired.

“The [Soviet] objective of the cold war is to divide the countries of the West, to isolate the United States, and to win the undeveloped countries to communism.

“Assuming that Britain’s negotiations to join the Common Market are successful, it is believed that all or nearly all of the Western European OECD countries will become affiliated with the European Common Market.

“There are seven of them already in the Common Market—the six original countries, and Greece was admitted on an associate basis. So that only leaves 11. And the majority of that 11 have already announced that they would seek affiliation if Britain’s negotiations are successful.

“If, then, the United States and Canada should associate themselves with the trade aspects of the Common Market movement, the Soviets would face a united West, with a political and economic aggregation so powerful that their cold war objectives could not be realized.

“On the other hand, if the United States stands aside, the West would be divided, the United States would be isolated, and the Soviets would have an open road to the underdeveloped countries.

“In any case, we must reduce the barriers to trade among the Western nations and the underdeveloped world because this is the only real way we have of solving our balance-of-payments problem, and protecting the dollar against devaluation. This will allow us to export more, it will help keep United States costs down, and it will take away the artificial incentive Americans now have for locating their new plants in Europe and thus exporting jobs to Europe.

“The second point which I feel can hardly be overemphasized relates to these same non-Communist underdeveloped countries. There are about 100 of them, with half of the population of the world. Half of these underdeveloped countries, with about 1 million of population, have been born into the world since the end of World War II. Even in normal times it would be extremely difficult to assimilate these inexperienced baby countries into the world family of free nations.

“It is my considered opinion that this it will be impossible to do so unless the rich industrialized nations of the West join together in an enterprise dedicated to raising the productivity and standard of living of the poor countries.

“It is my opinion that this narrowing of the economic gap between the two groups of countries can be done only by measures of substantially increasing the volume and the value of the exports of the underdeveloped countries.

“To accomplish this, the industrialized West must establish a system of free trade on the exports of raw materials of the underdeveloped countries.”

The Atlantic Convention was held in January of 1962. Citizen delegates from NATO nations acting without official instruction drafted the Declaration of Paris which called for the establishment of a “true Atlantic Community.” The U.S. Citizens Commission on NATO later called for the transfer of national sovereignty to transatlantic institutions. Their vision mirrored the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) rather than the federalist structure of the United States.

President Kennedy refused to let go of the federal Europe first doctrine—which was dependent on British membership in the ECSC. French President Charles de Gaulle rejected President Kennedy’s Anglo-American design for a united Europe augmented by an Atlantic partnership. General de Gaulle opted to pursue independence and grandeur for France with the encouragement of the Soviet Union. This did not stop Kennedy from openly declaring his support for an eventual union of all free men on July 4, 1962.

After President Kennedy was assassinated, and Senator Estes Kefauver unexpectedly passed away, Streit and company resurrected the Atlantic Union idea in the U.S. Congress under the leadership of Representative Paul Findley and Senator Frank Carlson. They were supported by a slew of influential Senators and Representatives in leadership positions. By 1968, all presidential contenders, other than Ronald Reagan, endorsed the Atlantic Union idea—Barry M. Goldwater, Hubert Humphrey, Robert Kennedy, Eugene McCarty, Richard Nixon, and Nelson Rockefeller.

After Nixon was elected President, the Atlantic Union idea experienced a legislative revival in the U.S. Congress. Streit and company advanced Atlantic federalism as a way of solving the monetary crisis facing the West while advancing federal trade between Atlantic nations—and eventually the world. Federal trade implied that all nations within the Atlantic Union would agree to abide by common rules and regulations adopted by the Atlantic federal government. The United States of Atlantica would then establish common foreign and economic policies designed to encourage developing nations to adopt Western institutions and join the enterprise.

The U.S. House of Representatives came close to bringing the Atlantic Union resolution to the floor for a deciding vote in April of 1973 after 197 members of the House voted to consider it. Ironically, Woodward and Bernstein—and the Washington Post—can take some credit for this outcome. President Nixon, after all, was unable to twist arms once the Watergate scandal erupted in 1972. Perhaps Nixon’s support for the Atlantic Union idea played a role in his political demise? What happened next may provide a clue.

In October of 1973, the Trade Reform Act was introduced and later passed in December of 1974. This was partly due to the influence of the Trilateral Commission under the leadership of David Rockefeller and Zbigniew Brzezinski. The passage of the Trade Act of 1974 was a major game changer. Under the Act, the U.S. Congress delegated “fast-track,” trade negotiating authority to the President of the United States. This put tremendous power in the hands of the President as the age of globalization was on the horizon.

Multinational corporations (MNCs) had a motive to kill the Atlantic Union idea. President Nixon and the Democratic Party gave them an artificial reason to seek regulatory emancipation after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Occupation Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) were established in 1971. After the Trade Act became law, MNCs were in a unique position to take advantage of regulatory inequality around the world to consolidate their economic power.

Fearing globalization without representation, checks, and balances, Representative Paul Findley, and other Atlantic federalists in the U.S. Congress, attempted once again to pass the Atlantic Union resolution. In April of 1976, 164 members of the House of Representatives favored exploring the establishment of an Atlantic Union based on federalist principles. President Ford, who consistently cosponsored the Atlantic Union resolution as a member of the House, likely would have signed it.

The Atlantic Union resolution was not reintroduced during the Carter administration. Carter, after all, was a Trilateralist who placed his economic focus on the Pacific, rather than Atlantic, area. Representative Findley attempted to resurrect the Atlantic Union idea in 1980 after George H. W. Bush was elected Vice President of the United States. It was worth a shot as Bush introduced an Atlantic Union resolution in December of 1969. President Reagan, however, was unwilling to entertain globalist schemes.

Clarence K. Streit passed away in 1986. You can explore the history of the Atlantic Union idea in greater detail at www.universalu.org.