A Brief History of Corporate Social Responsibility—and Why It Must Stop

CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) gained notoriety with Howard R. Bowen’s 1953 publication Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, and although times have since changed and CSR has taken on various forms, a constant question remains unchanged.

What is the role of business in society?

Some claim that a greater focus on corporate social performance over corporate financial performance is now warranted, while others adhere to a more classical viewpoint, siding with Theodore Levitt’s assertion that business should simply aim to achieve material gain while operating in good faith. Levitt, a German-American economist and professor at the Harvard Business School, spoke of “The Dangers of Social Responsibility” in a 1958 Harvard Business Review article. He posited that profit maximization over the long term should be the primary goal of business as this would have a spillover effect improving the wellbeing of society.

The propensity to exchange to benefit oneself as a means for societal advancement was most notably espoused in Adam Smith’s 1776 magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations. Milton Friedman later drove this message home in his seminal essay in the New York Times Magazine about how the “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.”

Yet, the prioritization of self-gain has proven to be a hard pill to swallow for a culture that seeks emotional fulfillment via altruism. As such, businesses have not only been encouraged to engage in CSR, but also to harness it and pursue a higher calling.

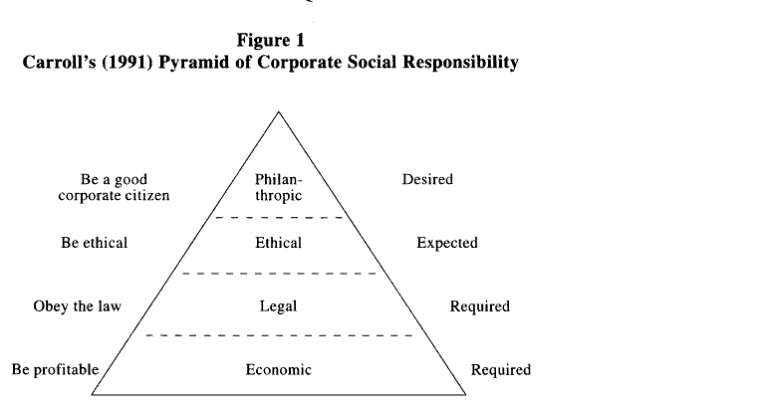

A prominent depiction of the evolution of business interest in CSR, along with society’s expectations for business behavior, is Archie Carroll’s CSR Pyramid, first published in 1991.

At the base of the pyramid is the economic responsibility for firms to be a productive element of society and contribute to the financial wellbeing of the organization. The next level concerns the legal responsibility of a firm to abide by the ground rules and regulations within the societies they operate. Further up the pyramid concerns a firm’s ethical responsibility, since laws are not sufficient in and of themselves for maintaining order. Indeed, societies establish mores and conventions which influence culture and communal interactions. For instance, it is not illegal to cheat on one’s spouse, but it does violate the institution of marriage; and to the same extent firms are wedded to the societies they are established within and should abide by certain expectations to maintain a healthy relationship.

The top of the pyramid is designated as the discretionary responsibility of philanthropy, wherein the company “gives back,” and this responsibility was posited to be “desired” by society rather than required.

The CSR Pyramid is still widely referenced and Dr. Wayne Visser, CSR professional, attests it to be a useful framework for managerial decision making. However, over time, the expectations for the top two tiers of the pyramid have expanded, and even what constitutes ethical behavior has evolved since Carroll’s publication.

In today’s competitive landscape, CSR constitutes a management strategy that goes beyond corporate giving and charitable networks. In fact, as defined by the United Nations, CSR is quite distinct from philanthropy given that it takes into consideration the social and environmental impact of a firm in addition to an economic impact.

An emphasis on the people, planet, and profit has become par for the course, and a variety of methods and forms of assessment regarding sustainability have come about for companies to prove their “good” work. John Elkington, who coined the term triple bottom line (TBL) for determining the social, environmental, and economic impact of a firm, claims TBL doesn’t go far enough and the business view of CSR is too narrow. He claims that firms should go beyond aiming to be the “best in the world” and instead aspire to be the “best for the world.”

What is “best” and for whom it is best, though, is largely subjective and open to interpretation. For instance, some social issues are undebatable, such as the desire to end world hunger, but the means for addressing them are usually complex and contestable.

Nevertheless, corporations are viewing themselves as social stewards with a moral charge, and this is an important shift to note, particularly since it is being driven by public opinion.

A 2018 study reported that 78 percent of Americans believe companies must have a positive societal impact beyond their productive purpose, and 77 percent of Americans “feel a stronger emotional connection” to purpose-driven corporations. Companies are responding to public sentiments and reinforcing such expectations through cause-related marketing campaigns and social labelling schemes, and this is a worrisome matter given the potential to compound the issues at hand.

Unlike the stages of the CSR Pyramid, which tended to be industry oriented, firms stretching beyond their domain of competence to prove themselves as worthy contributors to society at large (rather than streamlining efforts toward core stakeholders) is disconcerting for shareholders and distracting for budding entrepreneurs.

The spearheading of virtuous ventures and advocacy advertising show no sign of slowing down—and it won’t, until social pressure shifts back to value rather than virtue.

This article was originally published on FEE.org